and reach thousands of daily visitors

and reach thousands of daily visitorsRecently, research and clinical efforts towards merging the growing body of evidence in the field of stress neurobiology with the psychosocial effects of child maltreatment have been quite productive in narrowing the translational gap between biology and clinical practice. Despite these gains, many questions exist regarding how Child and Youth Workers (CYWs), clinicians and therapeutic programs should integrate brain and developmental psychological research into existing practice. Still, other questions arise concerning the usefulness of neuroscience in enhancing a practice’s effectiveness and efficiency. The article describes an example of a therapeutic program that blends current stress neurobiology, developmental psychology and statistics with current evidence-based psychosocial approaches with maltreated children.

Introduction

The quest to understand the brain and advancements in neuroscience,

technology and accompanying research has contributed to bridging the gap

between the behavioral sciences and developmental psychology. We have

been curious about the brain for a millennium and recent findings can be

compared to the discovery of a new frontier; similar to space

exploration. The advancements in the medical field are celebrated in the

media and research findings are found in magazines we subscribe to

and/or find in waiting rooms. We are beginning to understand the frontal

lobe, what makes us moral and the biology behind the impact of trauma.

We do not have to be neuroscientists to recognize that our interventions

and approaches are evolving to incorporate a multidisciplinary and

evidence informed methodology.

Anecdotally, many of our colleagues who are Social Worker and Child and Youth Counselors who have worked in the field for a minimum of five or more years, have recognized that the children they presently work with have more intense and multi-dimensional issues. The developmental and psychological impact of child maltreatment on our current child-in-care (CIC) population is evidenced in the identification of special needs, poorer treatment outcomes, and mental health concerns. In summary, the research evidence is showing that CIC who have experienced trauma and abuse face challenges in virtually every aspect of their daily lives; at school, in social situations, in the community, and at home.

Firstly, many children-in-care (CIC) may have mental health needs that are qualitatively and quantitatively different from the general population of children. Canadian research cites prevalence estimates of emotional and behavioral problems amongst children in foster care rising from 30–40% in the 1970–80s, to 48–80% in the mid-1990’s (Stein et al, 1996). More recently, Trocme and Chamberland (2003) found that endangered child development, or a lack of developmental learning opportunities, was the major reason for child services intervention for 75% of victims of maltreatment. Trocme and Chamberland argued that the sequelae of maltreatment was not sufficiently emphasized and/or addressed by the child welfare system.

Still more research has established that child maltreatment can lead to many psychosocial dysfunctions, making it a major risk factor for many emotional problems, behavioral difficulties, health problems, mental health disorders, delinquency and substance abuse (Kilpatrick, et al., 2000; Kilpatrick, et al., 2003; Rodgers, et al., 2004; Kauffman Best Practices Project, 2004). Based on his research in child welfare, Leschied (2004) has shown that CIC are over represented in school suspensions, learning disabilities, and provincial school drop out statistics, attention disorders, aggressiveness, delinquency, substance abuse, mental health disorders and mental health services. What is more, increasingly younger and greater numbers of children and youth require mental health services, where in Ontario 1 in 5 children are identified with a mental health concern.

Over the last decades, the Ontario Children's Aid Societies have done their utmost to place “hard to serve” children and youth in appropriate settings. However, due to financial constraints, inadequate resources, funding and services, the Ministry of Child and Youth services in Ontario have initiated a positive change within child welfare practice, a transformation agenda (2007). The “Differential Response” is child and family centered, community driven and situated, and accentuates family and systems strengths. The Differential Response tasks agencies to develop approaches which are individualized, socially inclusive and evidence-based. Child welfare workers are revisiting their clinical tools and engaging alternative dispute resolution methods such as family group decision making, and mediation. This transformation agenda includes a multidisciplinary approach, wrap around services and assessment of strengths as well as risk factors.

The work of Leschied (2004) and Trocme and Chamberland (2003) suggests that child welfare services should focus equally on endangered child development as well as protection and prevention of recurrence of child maltreatment. The ECHO model is an example of what developmental psychology could bring to child welfare. Although child welfare is not in the business of education, or providing children's mental health treatment, research argues that CIC should be provided with the opportunity to learn and practice essential skills necessary to reach their full academic and social potential.

The neuroscience of child maltreatment

Psychology’s views on child maltreatment have come a long way from the

groundbreaking work of Kempe et al. (1962) and Caffey (1972), who first

hypothesized that the psychological and developmental disabilities

observed in physically abused children were caused by forceful shaking

and blows to the head. From these initial perspectives, arose many

others, which appeared to fill-in the explanatory gaps between theories

(for a succinct history of the pioneering studies regarding child abuse,

see Carrey et al., 1996). The current perspectives on child maltreatment

seem to have shifted from the obvious (blows to the head and vigorous

shaking), to more subtle and complex explanations that use knowledge

from many other academic disciplines, such as biology, genetics,

physics, sociology, psychology, and evolution to form one general theory

explaining the underlying mechanisms behind the effects of chronic

childhood stress and maltreatment.

There may be many reasons for this shift in perspective, but this movement towards convergence of perspectives has been described by some as “Ionian Enchantment”; an expression meaning a belief in the unity of sciences (Holton, 1995). Arguably, neuroscience, which can be viewed as an amalgamation of many sciences (biology, statistics, psychology, chemistry, physics, and mathematics to name a few), has expanded psychology’s perspectives on chronic stress and maltreatment by synthesizing fact-based theories from various disciplines with neural correlate evidence in attempting to explain the physiological, social and behavioral ramifications of chronic stress and maltreatment, especially on the developing brain.

Brain imaging and child maltreatment

Although it can be argued that every child entering the child welfare

system experiences some level of trauma (Falmularo et al., 1996),

debating against the effects of chronic stress and maltreatment on the

developing brain is more difficult. With the advent of brain imaging

technologies, researchers have uncovered that child maltreatment and

chronic stress may be associated with developmental issues in brain

areas thought to be involved in learning, memory, attention, emotional

regulation, and, higher cognitive and social functions, brain structures

like the amygdala, hippocampus, corpus callosum and prefrontal cortex

(Carrion, et al., 2001; Teicher et al., 2003; Teicher et al., 2004;

Teicher, et al., 2006).

Caveat to brain research: Multifinality,

equifinality and variability

Despite exciting and convincing evidence that abuse and neglect are

associated with brain anomalies in children, it is important to keep in

mind that the observations and explanations regarding the underlying

mechanisms of many of these neurodevelopmental, cognitive, and self-

regulation issues are at the preliminary stages of research. What is

more, researchers in the field are quick to point out that chronic

stress and maltreatment are not the sole causes of brain anomalies in

this vulnerable population, many other causes can affect brain

development including the child's age, gender, temperament and/or

disability (Manly et al., 1994).

Even though the field of psychology and neuroscience is being bombarded with research articles and neuroimaging evidence regarding many psycho-pathological, psychosocial, and neurodevelopmental conditions, it is important to keep in mind two concepts: multifinality and equifinality (de Haan, et al., 1994 as cited in Glaser, 2000). An example of multifinality is when two children appear to be exposed to similar environments, but lead to different behavioral outcomes. Equifinality, on the other hand, is a developmental psycho-pathological concept that a mental health disorder may have several different causes (Barlow, et al., 2006). In summary, correlation does not mean causation.

Another caveat to keep in mind when evaluating brain research pertaining to children is that brain development is highly variable across individuals, and there seems to be considerable overlap among male and female, typical and neuropsychiatric populations, and among young and old (Lenroot and Giedd, 2006). This variable brain development spans the first 15 years of life and grows in the rostral-caudal direction (Thompson, et al., 2000), where significant remodeling of gray and white matter continues into the third decade of life. What is more, Lenroot and Giedd state that brain variability is so great in children and adolescents, that healthy normally functioning children at the same age could have 50% differences in brain volume, and for this reason alone researchers should exercise extreme caution when regarding functional implications of absolute brain sizes.

In addition to this neuroimaging evidence, Casey et al., (2000) found that the prefrontal cortex is one of the last brain regions to mature, and support the contention that attention and memory continue to develop physiologically and behaviorally throughout childhood and well into adolescence. Adding to this variability is the developmental make-up and histories of children, which encompasses genetic predisposition as well as experience-expectant and experience-dependent maturational processes of the brain (Greenough & Black, 1992).

In summary, correlation does not mean causation. For this reason, many in the field of psychology contend that clinicians do not need to understand neuroscience to deliver interventions such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy, to know that a treatment approach is effective. So why consider brain science?

Why brain science?

Nelson, deHaan and Thomas (2007) offer three answers to the question “Why brain science?”

Thinking of behavioral development in the context of neuroscience may provide a form of biological plausibility to existing or subsequent models of behavior.

Viewing behavioral development through the lens of brain science may shed new light on the mechanisms that underlie behavior, thereby moving psychology beyond the level of description to the level of process.

Neuroscience permits us to move beyond simplistic notions of behavior, providing clinicians with a more sophisticated understanding on how specific experiences (approaches, interventions) can influence specific brain circuits, which influence particular genes, which influence brain functions, which then influence how a child behaves.

Others, like Aron and Zimmer (2005), argue that the barriers between research and application have not yet been addressed or dismantled, leaving in its path wasted resources and ineffective application of behavioral science and health advancements. Because of the rise in costs and accountability for caring for Ontario’s children, child welfare and children's mental health agencies should consider how best to incorporate new developmental scientific research into current approaches with children, making these more developmentally appropriate and allowing brain research to inform clinical practice rather than just compliment it (Aron and Zimmer, 2005).

The ECHO Model

Rationale behind the ECHO Model

The ECHO model provides an Effective, Comprehensive, Holistic and

Objective approach towards enhancing academic and social functionality

in children. It was created in response to the need for an in-house,

cost-effective, caregiver and child centered program that addressed a

wide variety of developmental, social and emotional management issues

that affect many CIC. Traditional approaches, such as behavior

modification seemed to have limited effects and appeared to focus on

taking away privileges and limiting the child's access to social and

academic settings until the desired behavior was observed.

Because learning is experience dependent, the ECHO model’s philosophy is to optimize a student’s academic, social and emotional management learning opportunities in different environmental settings, such as the classroom setting, the recess setting, deskwork setting, and group work setting. Another objective of the model is to assist students in developing essential academic and social skills to enhance their overall independent functionality. The target age range in which ECHO was designed around, ages 8–12 years, was chosen because some of the exciting and cutting edge neuroscience findings suggested that children within this age range experience a second wave of neuronal rearrangement of sorts and an increase in brain activity in the frontal regions of the brain, the area reportedly involved in the integration and coordination of auditory, visual, tactile, olfactory, gustatory, social, and environmental input with behavioral output, as well as working memory, attention, planning and organization. (Paus, 2005; Anderson, 2003).

That a second wave of neurodevelopment occurs during periadolescence becomes a remarkable finding as it may offer child clinicians and therapists who address cognitive, academic, social and emotional management issues in CIC a possible second window of opportunity in which to remodel and/or enhance connectivity in the area of the brain responsible for the regulation of abstract reasoning, problem solving, working memory, response inhibition, and attention allocation (Gazzaniga, Ivry and Magnum, 2002; Casey, Giedd and Thomas, 2000). Providing psychoeducational programming that is experientially- based and focused on enhancing academic, behavioral, social and emotional regulation skills during this optimal developmental period may enhance clinicians” effectiveness in addressing these critical issues in CIC. The ECHO model was designed in an attempt to take advantage of this developmental window by offering evidence-based psychoeducational programming and real time “coaching” to CIC with psychosocial, developmental, academic and emotional management issues.

Although this approach is merely at the speculation stage, preliminary evidence suggests that psychosocial approaches can have “real” effects on the brain (Goldapple et al., 2004; Prasko et al., 2004; Brody et al., 2001; Martin et al., 2001).

Function of the ECHO Model

Every student is physically, psychologically and socially unique. The

function of the ECHO program is to observe, evaluate, strategize and

resolve general academic, behavioural, and emotional management issues,

which may in turn limit students' general developmental, learning and

socialization opportunities (Fraser, 2004). The approach offers students

who possess these issues a means of learning, practicing, and refining “critically appropriate” functional behaviour in a non-threatening,

enabling group environment where the student-to-facilitator ratio is

2:1.

ECHO programmatic design

ECHO’s programmatic design is unique in the fact that it has merged

developmental and psychological research and data collection into

existing psychosocial approaches. Various evidence-based models and

approaches, such as the Kazdin (2003) Problem Solving Skills training

model, Lochman et al.(1993) social skills program, progressive muscle

relaxation and meditation, a variation of Applied Behavioural Analysis,

and statistics (univariate and multivariate) are combined and applied to

teach students essential academic, social and emotional management

skills. Coupling these in this manner optimizes the ECHO facilitators” ability to build and exercise key developmental domains shown to be

affected in this vulnerable population, optimizing the number of

learning opportunities for each individual student.

Data collection and statistical analysis are an important component of the ECHO model which are essential to determining the program’s overall effectiveness and student short-term and long-term outcomes. The program’s facilitators collect detailed information regarding students' academic, medical, clinical, and personal history; facilitators also uses quantitative measurement tools to monitor the child's progress before, during and after their participation to the program. Observations on the student’s programmatic progress in eight proxies or contrived environments simulating the academic setting are also collected for each session (16 sessions in all). The data collected also guides ECHO facilitators and their interventions with participating students, allowing facilitators to evaluate the effectiveness of individualized student therapeutic programs, session by session, in the psychomotor, cognitive and affective developmental domains in addition to the eight proxies.

The model also assists students in generalizing newly acquired skills to other environments by using a wraparound service delivery model where a multi-disciplinary team consisting of foster parents, biological parents, Child Care Workers, Family Service Workers, Child and Youth Counsellors, teachers and children's mental health clinicians, is assembled and roles identified for each team member. The main objective here is that to be successful in resolving a particular student’s academic, social, and emotional issue(s) requires a collective, collaborative effort from all of the aforementioned parties.

ECHO Model assumptions

The model’s assumptions may also be different from other programming

that addresses academic and social issues. ECHO does not assume that

that the child has the ability to produce any academic work, use

expressive and receptive language effectively, or even that he/she wants

to attend the program, the only assumption is that the child does not

pose any safety issues towards themselves, staff or others.

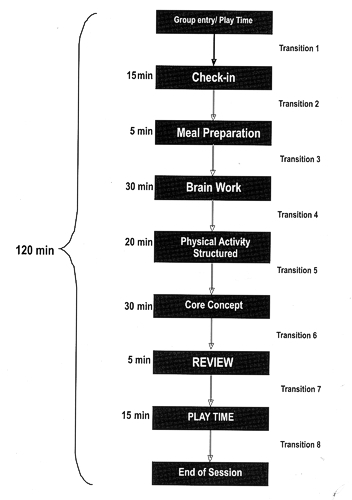

FIGURE 1

Typical ECHO session

ECHO curricula consists of eight weeks of programming, two times per

week – two hours/session – for a total of 16 sessions. It begins by

first introducing students to the importance, purpose and identification

of rules (2 sessions); subsequent sessions that follow build upon and

incorporate skills learned in previous sessions and proceed in the

following order: communication skills (2 sessions); problem solving (2

sessions) and conflict resolution (2 sessions) using an adapted version

of the Problem Solving Skills training model (Kazdin, 2003); coping and

relaxation strategies (2 sessions), hygiene and healthy lifestyles (2

sessions); and interpersonal/intrapersonal skills (4 sessions) using an

adapted version of the Social Skills Program (Lochman et al., 1993).

A typical ECHO session (Figure 1) consists of several different types of activities and settings. In all, there are nine planned activities and eight transitions. What is more, there are three general proxies (academic, group work, and play time) in which students get to exercise their academic, group, and play-time skills. All activities and core concepts (rules, communication, problem solving modules, etc.) integrate three learning domains to optimize each and every child's success and learning. The three domains and the types of activities found within these are:

Psychomotor domain. These activities focus on fine and/or gross motor skills exercises through physical education (PE) activities, writing/printing exercises, coloring, completing mazes, rhythm and dance, cardiovascular exercises, breathing and relaxation exercises (post PE), model building, arts and crafts.

Cognitive domain. These focus on the development and refinement of expressive and receptive language, reading, writing, comprehension, arithmetic, word problem-solving, abstract reasoning; categorization, phonics, declarative memory, sequencing and patterning. What is more, the students learn strategies that enhance studying and work output through facilitators demonstrating functionally adaptive work strategies, while positively reinforcing the child's motivation towards school work.

Affective domain. These activities focus on the child's interpersonal and intrapersonal skills. Activities include: communication strategies, self-concept, group work strategies, social and emotional attunement exercises (matching emotional reactions to social contexts and social cues, social and emotional decoding exercises, etc.), and self-identification of antecedents that lead to anger or frustration type behavior.

ECHO facilitators' tasks during the sessions entail teaching and building upon the each individual student’s work output, expressive and receptive language, problem-solving, emotional management, social skills, and frustration tolerance abilities using a graded, didactic approach that exercises a student’s ability to function independently and appropriately within the three general proxies (academic, group work, and play time). At the conclusion of every ECHO session, the facilitators complete the ECHO Session Functionality Scale (SFS), a tool that assists facilitators in monitoring each students' work output, on-task behavior, ability to transition between activities, expressive and receptive language use with peers and facilitators, problem solving abilities, frustration tolerance, and participation during each session; the SFS also keeps track of the approaches facilitators used that seemed to be successful with a particular student.

Although the concept is in its infancy, the main objective of the program is that the extra learning opportunities provided by ECHO may partially compensate for the CIC’s lost or limited learning opportunities due to behavioral, emotional, or social issues.

Conclusion

The ECHO model has been manualized and is currently being evaluated both

qualitatively and quantitatively through a collaboration with the

Laurentian University School of Education and the Children's Aid Society

of the Districts of Sudbury and Manitoulin. The program has also been

focusing on a best-fit for-service approach to providing and evaluating

children's mental health and child welfare services. The objective of

the current research, as well as the continuous development of the ECHO

program approach is to provide the right services to the right family at

the right time.

References

Anderson, S.L. (2003). Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 27. pp. 3–18.

Aron, L. and Zimmer, C. (2005). The New Frontier: Neuroscience Advancements and Their Impact on Nonprofit Behavioral Health Care Providers. The Alliance for Children and Families.

Barlow, D.H., Durand, V.M. and Stewart, S.H. (2006). Abnormal Psychology : An integrative approach. Thompson-Nelson: Toronto.

Brody, A.L., Saxena, S., Stoessel, P., Gillies, L.A., Fairbanks, L.A., Alborzian, S., Phelps, M.E., Huang, S.C., Wu, H.M., Ho, M.L. and Ho, M.K. (2001). Regional brain metabolic changes in patients with major depression treated with either paroxetine or interpersonal therapy. Archive of General Psychiatry, 58. pp. 631–640.

Caffey, J. 1972. On the theory and practice of shaking infants. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 124. pp. 161–169.

Carrey, N.J., Butter, H.J., Persinger, M.A. and Bialik, R.J. (1996). Physiological and cognitive correlates of child abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 34. pp. 1067–1075.

Carrion, V.G., Weems, C.F., Eliez, S., Patwardhan, A., Brown, W., Ray, R.D. and Reiss, A.L. (2001). Attenuation of frontal asymmetry in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Society of Biological Psychiatry, 50. pp. 943–951.

Casey, B.J., Giedd, J.N. and Thomas, K.M. (2000). Structural and functional brain development and its relation to cognitive development. Biological Psychology, 54. pp. 241–257.

Falmularo, R., Fenton, T., Augustyn, M. and Zuckerman, B. (1996). Persistence of pediatric post traumatic stress disorder after 2 years. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20. pp. 1245–1248.

Fraser, M. (2004). The ECHO Program: Training Manual. The Children's Aid Society of the Districts of Sudbury and Manitoulin.

Gazzaniga, M.S., Ivry, R.B. and Mangun, G.R. (2002). Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the Mind. (Eds.). New York: Norton & Company.

Glaser, D. (2000). Child abuse and neglect and the brain: A Review. Journal of Child Psychology, 41,1. pp. 97–116.

Goldapple, K., Segal, Z., Garson, C., Lau, M., Bieling, S., Kennedy, S. and Mayberg, H. (2004). Modulation of cortical-limbic pathways in major depression: treatment-specific effects of cognitive behavior therapy. Archive General Psychiatry, 61, 1. pp. 34–41.

Goldman-Rakic, P.S. (1987). Circuitry of primate prefrontal cortex and regulation of behavior by representational memory. In V.B. Mountcastle, F. Plum and S.R. Geiger (Eds.), Handbook of physiology. The Nervous System: Higher Functions of the Brain (pp 373–417). Bethesda: American Physiological Society.

Greenough W. and Black, J. (1992). Induction of brain structure by experience: Substrate for cognitive development. In M.R. Gunnar & C.A. Nelson (Eds), Minnesota symposia on child psychology 24: Developmental behavioral neuroscience, (pp. 155–200). Hillsdale, NJ. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Holton, G. (1995). Einstein, History, and Other Passions. Woodbury, NY: American Institute of Physics Press.

Kauffman Best Practices Project. (2004). Closing the quality chasm in child abuse treatment: Identifying and disseminating Best Practices: Findings of the Kauffman best practices project to help children heal from child abuse. Charleston (S.C): National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center.

Kazdin, A.E. (2003). Problem-solving skills training and parent management training for conduct disorder. In A.E. Kazdin & J.R. Weisz, (eds.) Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (p. 241–262).. New York: Guilford.

Kempe, C. H., Silverman, F. N., Steele, B. F., Droegenmueller,W. and Silver, H.K. (1962). The battered child syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association, 181. pp. 107.

Kilpatrick, D.G., Acierno, R., Sauders, B.E., Resnick, H.S., Best, C.L. and Schnurr, P.P. (2000). Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 1. pp. 19–30.

Kilpatrick, D.G., Saunders, B.E. and Smith, D.W. (2003). Youth victimization: Prevalence and implications (NCJ-194972). Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Kumari, V. (2006). Do psychotherapies produce neurobiological effects? Acta Neuropsychiatrica, 18. pp. 61–70.

Lenroot, R.K. and Giedd, J.N. (2006). Brain development in children and adolescents: insights from anatomical magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral reviews, 30. pp. 718–729.

Leschied, A.W. (2004). Beyond Child Protection: Identifying the Behavioral, Academic, and Emotional Needs of Children in Care. Paper presented at Breaking New Frontiers Conference. Huntsville, ON., September 20, 2004.

Lochman, J.E., Coie, J.D., Underwood, M.K. and Terry, R. (1993). Study 1. Aggressive and rejected. Effectiveness of a social relations intervention program for aggressive and nonaggressive, rejected children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 6. pp. 1053–1058.

Martin, S.D., Martin, E., Rai, S.S., Richardson, M.A. and Royall, R. (2001). Brain blood flow changes in depressed patients treated with interpersonal psychotherapy or venlafaxine hydrochloride: preliminary findings. Archive of General Psychiatry, 58. pp. 641–648.

Nelson, C.A., Thomas K.M., de Haan M. (2006). Neuroscience of Cognitive Development: The Role of Experience and the Developing Brain. San Francisco, CA: Wiley Publishing.

Paus, T. (2005). Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 2.

Prasko, J., Horacek, J., Zalesky, R., Kopecek, M., Novak, T., Paskova, B., Skrdlantova, L., Belohlavek, O. and Hoschl, C., (2004). The change of regional brain metabolism (18FDG PET) in panic disorder during the treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy or antidepressants. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 25. pp. 340–348.

Rodgers, C.S., Lang, A.J., Laffaye, C., Satz, L.E., Dresselhaus, T.R. and Stein, M.B. (2004). The impact of individual forms of childhood maltreatment on health behavior. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28. pp. 575–586.

Stein E, Evans B, Mazumdar R, Rae-Grant N. (1996). The Mental Health of Children in Foster Care, A Comparison with Community and Clinical Samples, in Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 41. pp. 385-391.

Teicher, M.H., Andersen, S.L., Polcari, A., Anderson, C.M., Navalta, C.P. and Kim, D.M. (2003). The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 27. pp. 33–44.

Teicher, M.H., Dumont, N.L., Ito, Y., Vaituzis, C., Giedd, J.N. and Andersen, S.L. (2004). Childhood neglect is associated with reduced corpus callosum area. Biological psychiatry, 56. pp. 80–85.

Teicher, M.H., Samson, J.A., Polcari, A. and McGreenery, C.E. (2006). Sticks, Stones and Hurtful Words: Relative Effects of Various Forms of Childhood Maltreatment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163. pp. 993–1000.

Thompson, P.M., Giedd, J.N., Woods, R.P., MacDonald, D.J., Evans, A.C. and Toga, A.W. (2000). Growth tensor mapping: A rostro-caudal wave of peak growth rates detected in the developing human brain in the first 15 years of life. NeuroImage, 11, 5. Part 2 of 2.

Trocm”, N. and Chamberland, C. (March 20–21, 2003). Re-involving the community: The need for differential response to rising child welfare caseloads in Canada. Paper presented at the Fourth National Child Welfare Symposium, Community Collaboration and Differential Response. Banff, Alberta.

This feature: Fraser, M. and Robinson, B. (2009). Bridging Child and Youth Work with Brain Research: Enhancing Social and Academic Learning Opportunities for Developmentally-at-Risk Children. Relational Child and Youth Care Practice, 22, 1. pp. 64-72.