and reach thousands of daily visitors

and reach thousands of daily visitors“Through the eyes of counteraggression, all events in life take on a new meaning.”

Those who work with troubled youth do not begin the day by saying, “I’d better schedule some time this afternoon to be sarcastic to Sarah, to yell at Sam, to threaten Sylvia, and to smack Seymour.” Yet, staff frequently find themselves in counteraggressive struggles with their students. How do we explain adult counteraggression when our intentions are to help troubled students, not fight them? Is counteraggression a function of personal inadequacies, a lack of self-control, a derivative of early child-rearing experiences? Or is counteraggression a biological “instinct” that all humans possess.

Psychologists are guided by the principle that a biological explanation of behavior has priority over any psychological interpretation of behavior. For example, we are born into this world with powerful instincts, drives. and impulses that have been refined over thousands of years to guarantee the survival of our species. The drive to seek food by stalking and killing animals made us predators. The needs for water, shelter, and an available source of new gene pools made us assailants, rapists, and conquerors. Similarly, the need to protect our lives, families, food supply, and properties made us counteraggressive.

The skill and strength of being counteraggressive guaranteed that primitive humans could survive another day. It became an asset; and over the centuries, the law of the jungle was replaced by the law of the land. Counteraggression was reinterpreted as a necessary act of self-protection and self-preservation against attacks by barbarians, invaders and assassins. Walled cities and formidable castles were built to withstand any siege. Stockades were constructed along critical waterways to protect new settlements. And after WWII, the policy of the large nations was to be prepared militarily at all times and to let every nation know that there would be a massive retaliation against any attack.

Counteraggression can be seen in a nation's armies and a town's police force. It has become so much a part of the fabric of our society that it is difficult to recognize how counter-aggression has shaped our thinking and attitudes. Currently, we applaud politicians and police, who are tough on criminals. We would like them to solve our fears of being a victim in the same counteraggressive ways in which our military forces have dealt with our foreign enemies: “Let’s punish them!” The biological instinct for counteraggression exists in all of us. Perhaps even in our DNA.

Looking Beyond the Simple Solution of Punishment

We all wish for a psychological aspirin to relieve our worries and pains. We would like someone else to solve the problem of violence in our society. We want the police, the courts, and the prisons to do their jobs and to protect us from criminals. However, there is one area where we can influence aggressive behavior; that is to learn how to control our own counteraggressive actions.

The number one reason for the increase in student violence in schools is staff counteraggression. While staff do not initiate student aggression, they react in ways that perpetuate it. Staff counteraggression is a complex issue. It is part of our history. It is part of our society. But counteraggressive acts should not be a part of our helping process with troubled children and youth.

Fritz RedI (1966), in his study of delinquent youth, was among the first psychologists to write about staff counteraggression. He described the underlying reasons why staff become counteraggressive. I have taken his creative concepts and have expanded them for the next generation of professional helpers.

Seven Reasons Why Adults Become Counteraggressive

1. Counteraggression is a reaction to being caught in the student’s conflict cycle.

The most frequent reason for reasonable staff to behave aggressively toward troubled students is that staff become caught in the dynamics of the students conflict cycle. About 50% of staff's counteraggressive behavior can be explained by this cycle.

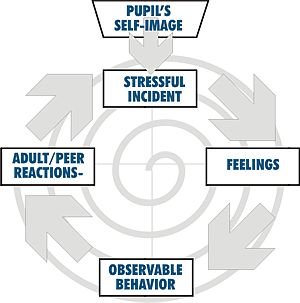

THE STUDENT'S CONFLICT CYCLE

The conflict cycle describes the circular and escalating behavior between a student and a staff member during a conflict. It teaches one of the most important principles of interpersonal behavior.

When a student is in stress, his emotions will echo in the adult. If the adult is not trained to own and to accept his or her counteraggressive feelings, the adult will act on them and mirror the student’s behavior. This means an aggressive student will always create counteraggressive feelings in the adult. Whenever adults act on these feelings, do what seems normal, and follow their impulses, the situation will become more emotional, irrational, and volatile. For example, when a student yells at a teacher and says, “I’m not going to do it!” the normal impulse and desire are to yell back, “Yes, you will do it!” Once this happens, the conflict cycle escalates.

During the heat of this battle, the staff member frequently refuses to back down or to acknowledge his or her role in furthering the crisis. The adult becomes locked into a rigid pattern of thinking. feeling. and behaving and tries to break down the door of the student’s resistance. The professional term for this adult behavior is “Retaliatory Resistance.” The adult retaliates because he or she has internalized the student’s aggressive feelings; and instead of using them as a diagnostic indicator of what the student is feeling, the adult acts on them and behaves counteraggressively.

Once this cycle begins, the adult fulfills the aggressive student’s prophecy: “All adults are hostile, and this incident is another example of a hostile adult who enjoys pushing me around.” Even when the student loses the battle with the staff member and is punished, the aggressive student wins the psychological war. The student’s irrational belief that adults cannot be trusted to treat him or her fairly is reinforced. Therefore, the student has no need to change patterns of thinking. feeling, and behaving toward adults now or in the future.

The knowledge of the Student’s Conflict Cycle enables a staff member to understand the source of counteraggressive feelings. That is, those feelings come from the student in stress. Adults who understand this can learn to accept these feelings, rather than to act on them.

2. Counteraggression is a reaction to the violation of our personal and cherished values and beliefs.

The second most frequent reason for staff counteraggression occurs when students attack and deprecate adults' internalized and cherished belief systems regarding how they should behave. Most of us have been taught to believe in selected middle-class values. We were told, hugged, kissed, and rewarded by our parents, relatives, and teachers whenever we showed any signs of being clean, neat, prompt, hard-working. honest, polite, precise, sexually reserved, emotionally controlled, and happy. In some families, these values were seen as virtues that could be attained only at the expense of rejecting their opposite values. For example, to be clean, we had to learn to dislike or hate dirt. To be neat, we had to view messiness as repulsive. To be prompt, we had to reject tardiness. To be hardworking, we had to spurn laziness or see it as a form of depravity. As we internalized the middle-class beliefs as cherished virtues, we also internalized the beliefs that being dirty, messy, tardy, lazy. lying, crude, sloppy, sexually impulsive. emotionally explosive, sullen, and angry are vices to be purged, repudiated, renounced, and despised. Unfortunately, that list includes many of the common traits of disturbed children and youth.

When troubled students look filthy and foul, are unorganized and untidy, procrastinate and turn in their assignments late, are not motivated to succeed, are passive, are unwilling to apply themselves, lie and cheat, are careless and have low standards, are abusive and insulting, are sexually primitive and mercurial, or are hot-tempered, excitable, menacing, glum, sad, and grim, their attitudes and actions can trigger strong emotions and counteraggressive behaviors in adults.

Staff members often define problem behavior as the discrepancy between what they observe and what they believe is proper and acceptable behavior. Unless we become aware of this, our internalized concepts of virtue and vice will continue to interfere with our effectiveness with troubled students. The solution to staff counteraggression begins with staff self-awareness, not with the student’s behavior.

3. Counteraggression is a reaction to being in a bad mood. Helping staff are not robots.

They have the same developmental, psychological, and physical stresses as all adults have. At times, their personal lives become overwhelming and emotionally exhausting. Their parents become ill and need special care. Their children have academic and interpersonal problems and need additional support. They have difficulties with their mate or friends. They have financial problems.

While these staff members usually are competent, dedicated, and supportive of their students, they feel rotten today. They have a bad taste in their mouth and a bitter attitude toward life. They cannot stomach the acid irritation of the normal and annoying behavior of their students and are ready to spew out their exasperation on any student who crosses them.

Then Jason decides it would be clever and fun if he added a little excitement to the classroom by making sounds with his armpits. The adult overreacts and becomes counteraggressive. After the heat of battle, the adult usually can acknowledge his role in the crisis and realize that he overreacted to the student because he was stressed and in a bad mood.

4. Counteraggression is a reaction to not meeting professional expectations.

The staff member views himself as a professional. He has earned his degrees and is certified to help troubled students. He understands the importance of developmental psychology, personality theory, group dynamics, and behavior management skills. He is not naive about the complexity of helping and usually has the insight to see trouble before it happens. But today, instead of using his professional judgment, he is in a good mood and agrees to let Warren and Jeff sit together, though he knows they rarely get along. He allows Matthew to keep the sea shells he brought to school because he promised not to play with them, though he also knows that Matthew is ADD. He permits a dodge-ball game to continue beyond the scheduled time because everyone is having a good time, though he knows it is an aggressive game. However, Warren and Jeff end up in a fight and have to be restrained. Matthew provokes his peers by saying, “I have something you can’t see,” until two of his classmates grab Matthew's shells while he screams, and Jennifer and Andrea are crying because Randy hit them with the ball during the final minutes of the game.

These conflicts could have been avoided if the staff member used normal strategies and skills. Instead, the adult becomes angry for not doing the “right thing” and reacts by taking it out on the students. “If they had behaved properly, I would not have all these problems. It’s all their fault!”

5. Counteraggression is a reaction to feelings of rejection and helplessness.

In every classroom we have a special relationship with one or two troubled students. We feel very compassionate and have a great deal of empathy for them. We understand them and are committed to helping them succeed, change, and improve. We are in their corner and ready to treat any of their psychological cuts and bruises. We are ready and willing to go the extra mile or stay an extra hour to support them. These students also appear to enjoy and respond positively to our involvement, so the relationship seems to be mutually satisfying and rewarding. Over time, however, this relationship begins to deteriorate. These “special” students become demanding and make unusual requests that we cannot grant. Most of all, they are suspicious of our intentions; and at times they misinterpret what we say.

How do we explain these changes in their feelings and behaviors? Why would they regress when they were making such clear academic and social progress?

Our first reaction is to say their behavior “makes

no sense". After all, we have not changed, and their programs have not

been altered. All we know is that they are treating us unfairly and we

do not like it! Considering all we have done for them, they should

appreciate our help, unless, of course, they are deliberately taking

advantage and exploiting our friendship and kindness! At second glance,

they seem to be looking for reasons to reject us and to discover why

their relationship with us and the progress they are making is a fluke

or a freak occurrence. They act like we are the enemy and not the

supporting adults.

What do these negative attitudes and rejecting behaviors mean to us and

these “special” students? For these students, the covert issue

motivating their behavior is the fear of closeness. The importance and

strength of our relationships are frightening to them. The problem is

not one of rejecting us, but of liking us too much. Prior to our

relationship, their irrational beliefs and defenses protected them from

having to change or modify their attitudes or behaviors. Now we come

along, and the warmth of our relationships over time melts some of their

defenses. Because of us, they are feeling exposed, fragile, and

ambivalent. They struggle between believing in their new and meaningful

relationship with us and wanting to hold on and protect their “pathological self.” They are experiencing a painful intra-psychic

battle. They want the warmth and affection of the relationships, but

they also remember the fear of being rejected and abandoned by adults.

While they are wrestling with this covert issue, the drama centers on

us. Believing too much sunlight makes a desert and not an oasis, they

test the relationship by trying to get us to reject them. If they are

successful, and we give up on them, they reaffirm their basic assumption

that the adults in their lives are hostile and uncaring.

This is a painful time for us because we feel rejected by the students we like the most. We feel angry and exploited. We have done more for these students than we have for any other student. But they are biting the caring hands that feed them. If we are not aware of their fear of closeness, we will do what seems natural and react with righteous indignation. We will tell them how ungrateful and inconsiderate they have been: and with justifiable fury. We will reject them.

By understanding troubled students' fear of closeness and their attempts to reject what they want the most, we can bring new insight amid hope into our relationships with these students and support them during this difficult stage of psychological change.

6. Counteraggression is a reaction to prejudging a problem student in a crisis.

A social structure exists in every school, and students peer are assigned and assume specific group roles, such as the leader, jock, nerd, mascot, lawyer, etc. One group role is the instigator or troublemaker. Everyone knows who this student is. His reputation is acknowledged by the staff, and peers follow him around like shadows on a sunny day.

If this student is involved in a crisis and the sounds of trouble are all around him, there is a high probability that this student will be prejudged as the instigator before all the relevant information is obtained. The staff member who intervenes is likely to say, “I knew it would be you!”

Whether you call this process flawed insights, faulty clairvoyance, or defective conclusions, it happens to the nicest of adults. Judgments are made that are not true, and the targeted student is accused of some act he did not do. In this sequence, the student becomes upset, and the adult is convinced the student is lying to protect himself. The result is an unfortunate incident that can turn into an ugly counteraggressive crisis.

7. Counteraggression is a reaction to exposing our unfinished psychological business.

Stress is inevitable in life. No one rides the waves of life without taking a serious tumble or thinking he might drown emotionally. No staff member enters the classroom or crisis room with a symptom-free history or has the perfect psychological fit to work successfully with all the students assigned to him. All caregivers have their pressures and problems. If the staff member’s parents were authoritarian, alcoholic, explosive, and unpredictable, he or she might grow up fearing aggression and aggressive people. When the staff member is faced with a troubled student who yells, curses, and threatens, the student’s behavior reactivates the adult’s childhood fears and feelings of vulnerability. The adult thinks only about how to escape from this unpleasant situation. The adult hopes the student’s behavior will stop. When it does not stop, the adult frequently is so upset he or she intervenes in a counteraggressive way.

Another example of how a teacher’s unfinished psychological business affected her ability to work with an aggressive student took place during the supervision of one of my graduate students. Ms. Powell was teaching at a day treatment program for seriously disturbed children, and she was complaining about how the boys in the oldest classroom, ages 10 to 12, seemed to delight in teasing the younger girls, ages 7 to 9. She was most upset by Tacuma, age 11. After she observed him provoking and tormenting Cheryl, age 8, on the playground, Ms. Powell said with irritation, “The teacher on duty didn’t do anything, although the staff say they protect children from verbal abuse.” I asked if she shared her observations with his teacher. She said she did not, and I urged her to talk to this teacher because this seemed like an important issue for her. I also suggested she think about why she was so upset by this incident and wanted Tacuma to be punished. She replied, “This is just like you! I come in describing an unfortunate student problem, and you turn it around and try to make it my problem!” I replied, “It may feel like I was accusing you, but I was only stating a thought.”

Ms. Powell left feeling unappreciated and angry. Two days later, she appeared in my office door and asked to talk with me. I invited her in, and she appeared embarrassed. In a quiet, reserved voice, she said: “Remember the incident I told you about Tacuma and Cheryl? Well, last night when I was reading, it came to me. I could hardly believe it! Cheryl was me and Tacuma was my older brother, Raymond! He would torment me and make me promise I wouldn’t tell our parents. He was cruel; and when I saw Tacuma picking on Cheryl, all those old feelings of anger welled up in me. If I were in charge, I would have punished Tacuma with pleasure.

Ms. Powell was able to identify and uncover a powerful and buried life event that triggered her counteraggressive feelings toward Tacuma. In reality, we carry our personal histories into our classrooms or activity rooms every day. Unfortunately, a few students have the key to expose our unfinished psychological business, provoking a counteraggressive response.

Summary

Staff counteraggressive behavior has no therapeutic purpose in helping

relationships with troubled students.

Counteraggressive behavior destroys the effectiveness of staff intervention and succeeds only in reinforcing troubled students” beliefs that all adults in their lives are rejecting and punitive. Our ongoing professional struggle is to become more aware of how the seven underlying reasons for counteraggression affect us personally. Preventing or controlling our counteraggressive behaviors does not increase our professional dedication or will power, but using our normal counteraggressive feelings as a signal does allow us to stop and think about why we are feeling so angry. Remember, with insight comes choice, change, and the changes to build more rewarding relationships.

Reference

Redl. F. (1966). When we deal with children. New York: The Free

Press.

This feature: Long, N.J. (1995). Why adults strike back: Learned behavior or genetic code? Reclaiming Children and Youth 4 (1), pp. 11-15