and reach thousands of daily visitors

and reach thousands of daily visitorsThe in-service training model presented here is based on principles drawn from the theory and practice of systemic and interactional psychotherapy. This does not mean that trainees receive psychotherapy. Rather, systemic and interactional principles are applied to the training process which theoretically allow for the creation of a context where changes in behaviour and thinking of trainees come from within the trainee group rather than being imposed on the group from the outside. The emphasis is on learning by trainees (and trainer) as opposed to teaching of trainees (Beker and Maier, 1981).

The ideas which I am going to discuss have arisen out of my attempts to operationalise systemic and interactional principles, firstly at an independent children's home, and then at a state-administered place of safety and detention. These ideas have evolved as I have learned from successful and unsuccessful attempts to put these principles into practice within the training situation.

Before discussing and illustrating the assumptions and principles used in this approach, a few introductory comments are in order. I agree with Vander Ven and Mattingly’s (1981) position that the role of in-service training is not to fulfil all the educational and training needs of child care staff. Nevertheless we often have to accept that this will be the only training which they receive. While I think that each child care setting should be free to create its own goals for in-service training, I have found the following goals meaningful.

To enhance cohesion and healthy

interpersonal functioning within the child care team. While

this is not strictly speaking a training function, the in-service

training process provides an invaluable opportunity for creating new

connections between child care workers, breaking down sub-grouping and

dealing with conflict. As this is an incidental by-product of the

training process rather than the obvious focus of attention, such issues

can often be dealt with in a relatively non-threatening way. Some of the

examples given later in this paper will illustrate how in-service

training can be used to achieve this aim.

To support and nurture trainees. Again, this is not strictly speaking a

training function. Nevertheless the training situation offers the

opportunity of “feeding" those who are continually feeding very

demanding children. This goal may be achieved most successfully when

training sessions achieve a blend of seriousness and good fun, and when

the positive rather than the negative aspects of child care worker

behaviour are emphasised.

To enable trainees to question and evaluate their attitudes and working methods, and to develop new ones. In working towards this I tend to emphasise one specific skill above all others, namely the ability of trainees to view themselves from a “meta-position". By this I mean that they learn to perceive situations as though they were looking at themselves from above, from where they would see that they and the children mutually influence one another in a recursive circular process. This aspect of the training model will be discussed in more detail later. It will be shown that looking at issues in this way allows for the development of skills to deal with a variety of on-the-job situations. Thus, in the model, course content is not ignored, but course process is emphasised in the hope that trainees will learn to think more holistically about their work (Beker and Maier, 1981). It is also hoped that trainees will become more aware of themselves and how they influence others.

To enhance the autonomy of trainees both as a group and as individuals. Naturally one hopes to see child care workers develop who can think and act systematically and independently in achieving the goals of the organisation. A further ideal is that these thoughts and actions will flow out of a feeling that “the way I’m working feels good for me because it fits my way of thinking and doing". I hope that this paper will provide some ideas about how this ideal may be approached.

As this model does not meet all the training and educational needs of child care personnel, it is hoped to stimulate trainees to learn more about work-related issues, e.g. by reading and enrolling for NACCW and other courses.

In introducing the principles used in this training approach, I shall also refer to various assumptions about how adults learn best.

Principle I: The trainer needs to understand and respect the organisational context.

Unless he does so, his goals, expectations and methods may be inappropriate.

It is easy to overlook the importance of the context when initiating an in-service training programme. To do so, however, can mean the death of a programme even before it starts. Let me illustrate this point.

As I have already said, I have done training in two different types of residential settings. My post at the children's home was created in response to a need expressed by the principal, social worker and the great majority of houseparents. Thus, the very fact of my appointment reflected a felt need for change from within the children's home, probably in response to pressures from both within and outside the home. The attitude of staff at all levels reflected the hope and expectation that they could learn from me in a way which would help them provide more effective physical and emotional care for the children. Given this context I could initiate an in-service training programme and feel confident of a high degree of involvement from the houseparents.

The situation at the place of safety and detention was very different. A national commission of inquiry into (white) child care resulted in pressure being applied from outside the institution to move from a custodial role to a role involving containment, assessment and even treatment of a vast cross-section of children varying greatly in degree of overt disturbance. In addition, new posts were created for professional staff such as myself, a psychiatric sister and an occupational therapist, who inevitably placed new demands on child care staff While the superintendent/social worker allied himself with the pressures for change, very few of the core child care staff shared his attitude. Quite understandably, most of the child care workers (who had previously been called institutional supervisors) responded with confusion and resistance.

Like any group of people facing pressure to change from outside the group, the child care worker sub-system could be seen as changing just enough to enable it to stay the same (Keeny, 1983, 1985). The trainer therefore had to be sensitive to the forces for change and stability within the child care worker group. The forces for change within the group were partially manifested to the trainer in the form of moves by some child care workers to de-emphasise their role as “controllers" of the children and moves towards a less hierarchical, more collaborative role (Hoffman, 1986) in relation to the children. The forces for stability were manifested by the majority of child care workers who clung tenaciously to their roles as “controllers" of the children.

In order to better understand the forces of stability within this situation, the trainer explored some of its history. It emerged that “institutional supervisors" (as the child care workers had been called) had been rewarded for controlling children rather than enhancing their growth. For example, they had been held responsible for allowing children to abscond or allowing them to create too much noise. It also emerged that “institutional supervisors" themselves had been “controlled" from above in the sense that they had unilaterally been given instructions which they had been expected to follow.

In the course of this paper practical ideas will be given on how a trainer in such a situation may systematically facilitate the development of new ideas and behaviour within a trainee group. I must point out that I have not always been successful in achieving this ideal.

Principle II: The effectiveness of the training will be largely determined by the trainees and how the trainer connects and evolves with them

While this point may seem patently obvious, I have seen courses which look good on paper fail precisely because of a lack of attention to this aspect of training.

In interacting with the trainees, the trainer needs to be accepted as part of the trainee group. He therefore needs to speak the language of the trainees, respect their values and resonate with their images and metaphors (Parry, 1984). At the same time, he must also maintain his position as someone who behaves and thinks differently to the trainees. If he becomes too much like the trainees he will be unable to challenge their “habits of mind", i.e. their “pervasive ways of thinking about themselves and their work" (Eisikovits and Beker, 1983). In striving to challenge the group while also being accepted, the trainer may have to be a bit like a dancer on a tightrope. This is particularly true of settings where the request for training does not come from the child care staff themselves. I shall now discuss some ideas on how the trainer can keep his balance on this tightrope.

During the first session I try to ensure that all trainees participate in generating ideas for the content issues to be dealt with in future sessions. A list is then compiled from which the group chooses what should be dealt with according to the perceived priorities of trainer and trainees. By this very simple act ideas are generated which

have meaning for trainees in their daily work and are therefore unlikely to be out of sync" with the context;

are likely to have meaning for the trainees who are therefore more likely to become involved;

help confirm the autonomy of trainees by giving them a feeling of control over some aspect of their working lives.

In addition, it may be useful to elicit trainees” ideas about what kind of training and supervision experiences have been useful or useless, and what they hope to experience during the course. This sensitises the trainer to possible successful and unsuccessful ways of presenting the course, as well as to the different learning styles of individual trainees. For example, some trainees learn best from discussions and didactic presentations, others by doing, experiencing and seeing.

At this stage I wish to make the point that from the outset this approach to in-service training is co-evolutionary (Penn, 1982). By this I mean that the content and process of the course evolves as a function of the interaction between trainer and trainees. Although the trainer through his knowledge in a sense directs the process, he does so in collaboration with trainees rather than as an outsider adopting a hierarchical stance (Hoffman, 1986).

I now want to give an example from practice of how a trainer may speak the language of trainees and respect their views without losing the ability to challenge the “habits of mind" of the trainees.

I have mentioned the setting where child care workers had been rewarded for “controlling" children and where the majority of child care workers therefore clung to this role. It was thus not surprising that the first two topics selected for training sessions were Discipline and Dealing with the aggressive, hostile child.

The trainer accepted that the question was a very important issue. However, in order to generate new ideas within the group, it was necessary to get trainees to look at discipline in a new way.

In asking questions about what was meant by discipline, it emerged that to the child care workers a lack of discipline meant something like “a failure by the child to respond to rules and instructions". Note the emphasis on the child as the problem for failing to respond to some external input (instructions and rules) which is unquestioned.

During the first sessions on discipline trainees were asked to look at themselves in the past and present and to identify areas where they had been “undisciplined", and areas where they were now self-disciplined. They then had to examine how they and others had unsuccessfully tried to instill discipline. They were also asked to explain for themselves how their self-discipline had emerged. The trainer also participated in this exercise which was aimed at helping trainees learn from their personal experience “"from the inside out" (Duhl, 1982). Like all of us, child care workers were once children and adolescents who were exposed to various forms of discipline which had varying effects on their lives. They are therefore in possession of much useful knowledge about discipline, but usually need someone to make this knowledge accessible.

The trainees were then asked to share their experiences as far as they felt they could, and discuss their conclusions. They arrived at a number of insights, the most important of which was that certain types of adult behaviours and attitudes were more likely to encourage positive responses than others. They also realised that discipline can never be forced on a child or adolescent from outside.

It is not suggested that new insights like these will on their own lead to improved practice. However, together with other training interventions they provide valuable ideas for discussion during further training and supervision sessions. As such they form part of the thread from which new practice methods are woven.

During the second session on discipline, a “discipline problem" was role-played and three groups of trainees were asked to observe:

The child care worker’s behaviour;

The child's behaviour;

The interaction between the two.

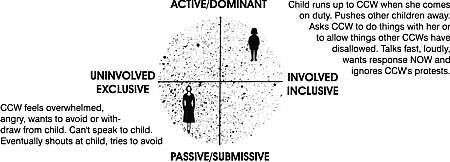

They were then asked to map the observed process using a simplified form of the Leary Interpersonal Circle (Duke and Nowicki, 1982; Kiesler, 1982).

Let me briefly digress to explain the use of the Interpersonal Circle. As applied to the role-play situation, trainees observe the child care worker’s reaction to the child's behaviour in terms of whether the process increases or decreases the level of involvement or the interpersonal distance between child and child care worker, and how it influences the respective activity/dominance level or passivity/submission level of the respective participants.

As can be seen from the example here, the trend in the relationship process can be mapped in a way that gives the trainee child care workers a meta-view of the process occurring between themselves and the children.

They can also he shown how they and the child behave in ways which mutually maintain the circular process. In the example given here, the more the child seeks attention, the more the child care worker tries to avoid her, which makes the child try harder for attention, which makes the child care worker more avoidant, and so on.

Having identified this process they can think of ways to influence this process in a positive way, depending on the needs of the child (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1

Example of use of Interpersonal Circle

Having role-played and analysed this process, it

was decided that the child obviously wanted and needed attention, but

should be helped to get attention without overwhelming adults and

children.

Strategy “for child care worker to take initiative by becoming more active and initiating involvement from her side, e.g. to surprise the child when coming on duty by running to her and greeting, hugging, talking to her; to set firm limits and to verbalise child's needs to have child care worker all to herself; to take child for time together later in the day.

The team working with the child also took steps to improve their teamwork and meet the child's underlying needs.

Having looked at the discipline problem in this way, the trainees suggested a number of different ways in which the particular child care worker involved could alter her behaviour so as to change the process of the discipline problem and simultaneously act therapeutically.

This whole exercise led to a change in the way the child care workers saw the discipline problem. Whereas they had initially defined the problem as a characteristic of the child (a failure to respond to rules and instructions), the problem became redefined as “how can I change my behaviour so as to influence the child's behaviour and the process occurring between myself and the child?" This view of the problem is of a higher level and of great pragmatic importance. It implies that child care workers accept that they themselves are part of the discipline problems which they face. This gives the child care worker the responsibility of doing something different in order to change the process, and opens up new choices for them.

In concluding this example, it can be said that the training process created an environment where trainees could act so as to increase the number of choices available to them in their work situation (Von Foerster, 1973). It can also be seen that the trainer started with material presented by the trainees and then “complexified" their thinking so that their usual “habits of mind" were expanded, but not challenged so much that they could not assimilate new ideas. This fits the Piagetian model of learning where new learning is based on previous learnings leading to greater differentiation of thought and action (Duhl, 1982). This approach to training assumes that adults (and children) learn best when they are exposed to many different sensory-motor-cognitive experiences such as acting, reflecting, seeing, feeling, hearing, describing, imitating, explaining, etc. (Duhl, 1982).

Let me give another example of complexifying the habits of mind of trainees so as to achieve learning. When requesting training sessions on “dealing with the aggressive, hostile child", the trainees asked, “What does it mean when a child behaves like that?" Itt exploring their ideas, I felt that they were overlooking the contextual meanings of this behaviour. The trainees were then asked to split into groups and think of the aggressive children with whom they had worked or were working. They were asked to make lists of all things that aggressive behaviour may mean within the institution. They produced 24 ideas, most of which reflected in some way the contextual aspect of aggressive behaviour (e.g. aggressive behaviour may mean that the child has been given conflicting messages by staff; that the child feels scared and insecure in a strange situation; that there are no other outlets to the frustrations of group living; that the child needs to push the child care worker away for some reason). Thus, in response to being asked to look at aggressive behaviour in a new way, i.e. hy looking really closely at their own question within the context of their work situation, trainees generated their own new ideas about this behaviour. From their own new ideas they were able to generate a comprehensive list of strategies for dealing with aggressive behaviour which they were asked to apply as they saw fit. We then followed up by looking at how they had applied these ideas. In doing so the child care workers could see concrete effects of their intervention on the behaviour of certain children.

I am not suggesting that the techniques I have described are new. What I am trying to demonstrate is that when one has a sound knowledge of one’s trainees and the training.

Principle III: The trainer has to adjust his input according to feedback from trainees just as trainees have to adjust their behaviour to that of the children in their work. In this respect the training situation is analagous to, or isomorphic with, the trainees” work situation. This isomorphism provides valuable opportunities to enhance learning.

The underemphasis on course content makes it relatively easy for the trainer(s) to adjust to the feedback from trainees so as to enhance learning. The techniques for doing this may be very simple. For example, if the trainer notices that some trainees are becoming bored by verbal discussion, the group can be activated to perform small group tasks or to do a role play The trainer can point out what he has done and link it to situations where child care workers have to deal with children who are becoming bored with activities.

Another example: if trainees fail to carry out homework tasks given by the trainer over a few sessions, the trainer can explore this issue while pointing out that the situation is similar to that where children fail to meet the hopes and expectations of staff Perhaps the trainer’s homework tasks were unrealistic in some way, just as our expectations of children sometimes prove to he unrealistic when we examine them closely. By making it clear that homework tasks are an essential part of training, but also eliciting trainees” ideas on how more realistic and meaningful tasks may he assigned, the trainer provides a model for how trainees may work with children or adolescents.

Another example occurred when the requested training topic was “conflict resolution of children's conflicts". In providing a conflict-resolution model (Vansteenwegen, 1976), the trainer got staff to practise implementing this model by using inter-staff conflicts. By doing this in an interesting way, some trainees were able to negotiate conflict situations directly with each other, something which they had never even tried to do previously Staff conflict became refrained as an opportunity to apply a new skill rather than something to he avoided.

I see in-service training then as working on many levels simultaneously, the one level being skill acquisition, and the other being the level of relationships between all involved in the training process. When working on conflict resolution skills, one is also working on staff conflict; when working on the skills of improving the self-esteem of children, one is also aiming to improve the esteem of trainees.

Some situations with which child care workers or houseparents have to work bear little relation to the training process. Nevertheless, without experiencing these situations in a “gut-level" sense, it is difficult for workers truly to appreciate what they are working with. In such cases it may he necessary for the trainer to create a situation in the training session which generates a real experience which will help improve their understanding of children. Thus, the isomorphism between the training situation and the work situation does not naturally exist “it is created.

An example of such a situation is the experience of the child or adolescent who is removed from home and placed in an institution such as a place of safety. When the topic of “helping children deal with the trauma of removal" came up, I had to create a situation which would in some way generate a wide range of feelings, including intense feelings of anxiety and uncertainty. This is how I went about it:

Eight of the ten trainees did not have driver’s licences and five of these eight trainees were over 48 years old and had never driven. This lack of drivers had created practical problems at various times. When the trainees arrived for this particular session, the superintendent said that he had to make an important announcement before in-service training started. He then read out a “letter" from Head Office which stated that by a particular date five months hence, it would be a work requirement for all child care workers to have valid driver’s licences. Everybody was to immediately report to the administration office and provide details of their driver’s licences or lack thereof. After the five-month period had expired, those who did not have licences would very regrettably lose their positions as child care workers. As management was aware of the importance of the issue as well as the anxiety it would create, it had been arranged that all child care workers would be taught to drive by the institution's driver (who had the reputation of being a frustrated Niki Lauda!).

After the necessary administrative procedures had been carried out and the trainees were given the opportunity to ventilate and finish their cigarettes, they were debriefed. Naturally they had experienced a wide range of feelings which included: fear of what lay ahead; panic; outrage; dazed disbelief; regret at missed opportunities in the past (to get driver’s licences); mistrust (about the proposed driving lessons); thoughts on how to escape the situation (one younger child care worker even thought of falling pregnant!); determination to face up to the challenge; pleased that the problem was being confronted. I do not need to point out the similarity between these feelings and those of children who are removed from their familiar surroundings and placed in an institution.

From this point the trainees firstly generated ideas on how the shock announcement could have been made to reduce the inevitable feelings of stress. Thereafter they compiled a list of measures which they and others involved in the removal process could take to deal with this difficult situation constructively Some of these ideas were subsequently adopted by management in refining admission procedures to the institution. Thus, not only is context considered as an important influence on in-service training, but in-service training can (and should) feed back to influence the context.

Again, this example illustrates the principle of learning “from the inside out" by immersion, reflection, analogy and experiencing through all the senses (Duhl, 1982).

PRINCIPLE IV: The trainer does not have unilateral control over the training process, the outcome of which is largely unpredictable

The trainer should therefore be flexible and not presume that his views

are always more “correct" than those of trainees.

Again, in this respect the training situation is analogous to the work

situation. When working with children, child care workers have to accept

that there is much over which they have no control. This is partly

because chance plays a significant role in the development of all people

(Shuda, 1986) and partly because the way children respond to us depends

so much on their own structural makeup (Dell, 1985), i.e. physical,

cognitive, psychological, experiential and interpersonal makeup.

The same applies to the training situation where the outcome depends on: firstly, what the context will allow; secondly, what the trainees can absorb and integrate; thirdly, the extent to which the trainer can connect with trainees and the context so that he is perceived as confirming and growth-enhancing.

This does not mean that the trainer should not have a plan. Indeed, he must know in what direction he wants to go and especially in what direction he does not want to go. He must also be acutely aware of how he wants to work. However, the trainer adopts the attitude that the most effective way of helping trainees to develop is to complement and “complexify" the ideas, behaviours and experiences of the group. He accepts that there is an inherent wisdom about some of these ideas “a potential which must be realised by the trainee group. I hope that the examples which I have given have reflected this viewpoint.

Another implication of this concluding principle is that being aware of the unpredictable nature of all human processes, the trainer is always on the look-out for the unexpected. The unexpected things which happen during in-service training are often very valuable. For example, after the exercise involving driver’s licences described earlier, the two child care workers who did have licences expressed great disappointment when they discovered that it was only an exercise and not a reality. They were often overloaded with demands because so few child care workers had licences. This provided a very useful analogy for children who are in some way burdened and who have hopes and expectations dashed when adults change their plans “something which was worth exploring. In addition, the whole exercise got some child care workers thinking very seriously about doing something to get their driver’s licences. Another exciting unpredictable issue is the effect of the training process on the dynamics of the trainee group which I have already mentioned (e.g. the improvement in group cohesiveness).

Cautionary comments

While I think that this approach has something of value, not only for

the in-service training situation, but also for supervision and

management situations, research is needed to systematically assess its

strengths and weaknesses. At some stage I hope to conduct some such

research. My aim in this paper has simply been to present a framework

from which you will each be able to take something useful.

Experience has taught me that to gain maximum effectiveness from this approach, middle and senior management must be involved in the training process, preferably directly or at least indirectly. This involvement ensures that the direction of the training process accords with the goals of the organisation. It also ensures that institutional policy can be adjusted when appropriate to accommodate the development of child care personnel’s skills and expectations. For example, staff may need and want individual or group supervision to help them consolidate new skills. Management needs to make provision for this.

Another point is that I think that two or more trainers would he more effective than one. It is difficult for one person to deal with the subtleties and different levels of process which emerge during training.

Finally, there may be some situations where some of the principles of this approach are not appropriate. For example, when working with a group of child care workers or houseparents who are completely new to the field, the trainers may have to plan certain aspects of course content in advance.

Bibliography

Beker, J. & Maier, H.W Emerging issues in Child and Youth Care education: a platform for planning. Child Care Quarterly 10(3), 1981, 200-209.

Dell, P.E Understanding Bateson and Maturana: toward a biological foundation for the social sciences. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 11(1), 1985, 1-20.

Duhl. From the inside out and other metaphors. Brunner/Mazel Publishers, New York, 1982.

Duke, M.P & Noisicki, S. Social learning theory analysis of interactional theory concepts and a multidimensional model of human interaction constellations. In: Anchin, J.C. & Kiesler, D.J. Handbook of Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Pergamon, New York, 1982.

Eisikovits, Z. & Beker, J. Beyond professionalism: the Child and Youth Care worker as craftsman. Child Care Quarterly 12(2), 1983, 93-112.

Hoffman, L. Beyond power and control: toward a “Second Order" family systems therapy. Family Systems Medicine 3(4), 1986, 381-396.

Keeney, B.P. Cybernetics of brief family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 9(4), 1983, 375-382.

Keeney, B.P. & Ross, J.M. Mind in Therapy, Basic Books, New York, 1985.

Kiesler, D.J. Interpersonal theory for personality and psychotherapy In: Anchin, J.C. & Kiesler, D.J. Handbook of Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Pergamon, New York, 1982.

Leyland, M.I. An introduction to some of the ideas of Humberto Matwana showing some of the connections between these ideas and the Milan School of family therapy. Unpublished paper, Institute of Family Therapy, London, 1985.

Parry, A. Maturanation in Milan: recent developments in systemic therapy. Journal of Strategic and Systemic Therapies 3(1), 1984, 35-42.

Penn, P. Circular Questioning. Family Process 2 1(3), 1982, 267-280.

Shuda, S. Stelselontwikkeling in “n kinderhuis. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis. University of Pretoria, 1986.

VanderVen, U. & Mattingly, M.A. Action agenda for child care education in the 80–s: from settings to systems. Child Care Quarterly 10(3), 1981, 279-288.

Vansteenwegen, A. Gevechtstraining in echtpaartherapie. Tydschrift voor Psychotherapie 2(1), 1976, 30-39.

Von Foerster, H. On constructing a reality. In: Preiser, W. Environmental design research II. Stroudsburg, Pa. Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross.

This feature: Powis, P. (1988). A process-oriented in-service training model for child care personnel, in Gannon, B. (ed.) Today's Child Tomorrow's Adult. Cape Town: NACCW. pp.23-32