This article presents an overview of conflict resolution; key concepts, including approaches to and styles of conflict management, are outlined and methods of effective conflict resolution are described. Unfortunately, many families of children receiving child care services cannot constructively resolve the conflicts that are an inevitable feature of family life. Ineffective or inadequate conflict resolution can adversely effect other aspects of family functioning; one way of helping such families is to teach them more effective methods of conflict resolution. Child care workers in family support programs are in an excellent functional position to provide such instruction. A combination of workshops and family-specific instruction is suggested as an effective approach to teaching families the skills of constructive conflict management.

Conflicts are present in many family situations and may occur between children, between spouses, and between parents and children. Conflicts develop when there are differences “between what people want to accomplish, the ways in which they pursue their goals, their personal needs, and the expectations they hold for each other’s behavior” (Johnson, 1986, p.199). Indeed, conflicts within families are inevitable and, in themselves, are not necessarily negative; problems arise from inadequate or ineffective resolution of conflicts. While many families can manage conflict, some families are unable to resolve conflict situations effectively. In families where conflict resolution is ineffective, negative feelings like anger or frustration may arise and chronic problems in family functioning may develop. More dramatically, conflict situations can intensify, leading to crisis or family violence.

If conflicts are handled well they can strengthen family relationships. If handled poorly they may create power struggles, hostility, resentment and disharmony. Ineffective conflict resolution is a factor in the problems that face the families of many children in the child welfare system. As suggested above, this may adversely affect other aspects of the family functioning. One way of helping such families is to enhance their ability to manage conflict situations more constructively by teaching them conflict resolution skills.

Child care workers who work in the family setting, for example, family support workers, are in an excellent position to help families develop more effective conflict management skills. Because they work with families and children in their natural environment, they are able to observe family members' conflict management styles and approaches to handling conflict situations. Their work places them in the position of being able to teach families the dynamics of conflicts and approaches to constructive conflict resolution. As well, they have the opportunity to provide family members with ongoing coaching, support and feedback relating to more effective ways of handling conflicts.

This article describes and discusses approaches to managing conflict and the personal conflict management styles which people typically employ. Such information is necessary if family members are to understand the dynamics of conflict situations and increase their awareness of how they manage disputes. With increased self-awareness, family members are ready to learn the methods of constructive conflict resolution which will be outlined in this paper. Approaches which child care workers can use to teach these skills to families will also be presented.

Overview of conflict resolution

Types of conflict

Conflicts are inevitable in family life. They develop for a multitude of

reasons and arise because of differences in values, needs and

expectations. Three types of conflicts have been identified: content,

value and ego conflicts (Gamble and Gamble, 1982). Content conflicts are

disagreements over facts or issues, such as whether to buy a station

wagon or a sedan. Value conflicts are based on differences in values.

They can arise, for example, in a situation where the mother has high

standards of cleanliness and the adolescent does not. Ego conflicts

occur when family members' perceptions of themselves become involved in

the conflict. As such, the outcome or resolution of the issue impacts on

participants' sense of self-esteem and worth. For example, a mother and

daughter may be arguing about curfew rules and mother may tell herself, “There is no way I’m giving in, because if I do she’ll always get her

own way. If that occurs, I'll be an inadequate parent.” The important

issue for mother is not when curfew will be or how strictly it will be

enforced but, rather, her perception of herself as a good parent. The

daughter’s ego investment in the same situation may relate to her

perception of herself as an independently functioning young adult who

can make her own decisions. Poorly resolved ego conflicts are very

detrimental to family relationships.

Approaches to conflict resolution

The three main approaches to managing conflict are avoidance, delay and

confrontation (Stepsis, 1974; Johnson, 1986; Adler and Towne, 1987).

These three approaches, illustrated in Figure 1, are described below.

Figure 1

(adapted from Stepsis, 1974)

Avoidance

Some people avoid conflicts. They tend to repress emotional reactions,

ignore issues, and not face up to disputed situations. Phelps and Austin

(1974) list five behaviors that are typical of persons who avoid

conflicts. These styles, with examples of typical cognitive statements

underlying them, are described below:

Approaching others as the underdog: “He isn’t going to listen to me so why bother trying to change his mind.”

Letting others make decisions: “I don’t want to be responsible for the consequences, so I'll let Mary decide.”

Fleeing or giving in: “Don’t yell at me anymore, I'll do what you want.”

Lack of self-sufficiency: “I’ve never made a decision on my own before, so I can’t decide alone.”

Responding with disrespect, anger or frustration: “Let him make the plans, I'll just continue doing things my own way anyhow.”

Avoidance is not usually functional since the conflict does not go away. Resentments are built up, feelings tend to be displaced on others and underlying problems within the family remain unresolved.

Delay

Delay or defusion is a second strategy which can be used to cool off a

situation. At times it may be useful to postpone confrontation, however,

too long a delay can create the same problems as avoidance. For example,

a parent may decide to postpone discussing an important issue such as

neglect of household chores with a teenager because the teenager came

home from school upset. She decides to wait for a better opportunity

since she does not want to get into an argument. However, she waits for

several days, all the while keeping her feelings and thoughts inside,

and becoming so frustrated that when she finally raises the issue she

begins by yelling at her son.

Confrontation

This is a third strategy which may be used. One meaning of the word “confrontation” is “to face.” Thus to confront an issue is to face up to

it and deal with it. It is in this sense that “confrontation” is used in

this paper. Depending on how it is carried out, confrontation may be a

negative process involving the use, or misuse, of power or a positive

process that involves negotiation:

The use of power creates a win-lose situation where one person wins and the other person loses. Phelps and Austin (1974) found that persons who used power made unilateral decisions for others, humiliated or produced defensiveness in others and, in some cases, even physically attacked others. An adolescent who bullies or pushes younger children into doing things his way or a traditional husband who makes all important decisions in the family without consulting others are examples of persons who use, or actually abuse, power. Such use of power often results in hostility, anger, frustration or defiance and a lack of commitment to goals established by others.

A second way to confront conflict is to negotiate, or skillfully manage the conflict to a mutually satisfying solution. Phelps and Austin (1974) found that those who negotiate treat others with respect, are direct in stating their own needs, help others express their needs and seek solutions which meet the needs of all parties. Constructive handling of conflicts can enhance and solidify family relationships. The approach may not always work but it avoids many of the negative effects produced by avoidance, delay or the use of power.

Conflict management styles

Each person has a predominant style or strategy for managing conflict. A

person's frame of reference for managing conflicts stems from their

values, feelings, self-concept, and perceived needs. This style is also

related to the social skills an individual has learned as well as to

feedback he or she has received in life.

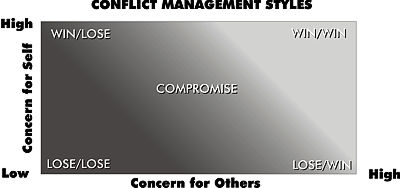

Figure 2 illustrates the five conflict management styles, which have been commonly described in the literature (Graham, 1980; Warshaw, 1980; Johnson, 1986; Adler and Towne, 1987). These styles represent a number of ways individuals can try to resolve conflict. Each style arises from a combination of a person's concern for self and for others. The conflict management styles, which are described below, are: Win-Lose, Lose-Lose, Lose-Win, Compromise and Win-Win.

Figure 2

(Graham, 1980)

Win-Lose

This is the style used by people who have high concern for themselves

and low concern for others. Their primary goal is to get their own needs

met and they use power to achieve this objective. Typical behaviors of

such persons include forcefulness, threats, demands, intimidation,

deceit and manipulation. Warshaw (1980) has identified the following

three types of Win-Lose personalities: Jungle Fighters, Dictators and

Big Mamma's/Daddy’s.

Jungle Fighters are charismatic, manipulative and consummate con-artists. They love to fight and keep others off balance by using intrigue, red herrings or double messages. Yet, at the same time, they may have good qualities such as ambition, tenacity, and creativity.

Dictators try to intimidate and are authoritarian in their approach to people. They tend to be rigid and expect people to listen to them. There is no right or wrong way, only their way! They can be demanding and threatening and often use interrogation and moralizing to get their way. Their assets may include efficiency, organization, and logical thinking.

Big Mamma's/Daddy’s are manipulative in their approach. They are nurturing and they try to convince others that what they propose is in the others' best interest. They have a consoling, reassuring communication style and they appear to be supportive as long as things go their way. Their caring, nurturing approach may be comforting to many individuals. However, they can become quite overprotective and stifle other people’s initiative.

Lose-Lose

The predominant style of people who have low concern for themselves

as well as low concern for others is Lose-Lose. Such people do not face

issues, rarely provide direct answers and avoid conflict. This is a

stance which often leads to both sides losing. Warshaw (1980) has called

Lose-Lose negotiators “Silhouettes,” suggesting that they seldom respond

outwardly to conflict. They use avoidance when possible and react to

disputes through silence. In conflict situations they tend to cause

frustration and confusion and, because they avoid dealing with

conflicts, underlying issues continue to brew.

Lose-Win

Lose-Win is the style that is characteristic of persons with a high

concern for others and low concern for self. In conflict situations they

have a strong need to maintain harmony and thus they avoid facing

issues, rarely state their opinion, and readily give in. These

individuals are described as “Soothers” by Warshaw (1980). In many

traditional families, females adopt this style, tending to avoid

confronting problems, showing a willingness to conform, and becoming

anxious in conflict situations. Individuals who use this style have a

difficult time say “No” or, as Warshaw has stated, “They blame

themselves too quickly and make concessions too early” (p. 51).

Consequently, their own personal needs are rarely met. However, they are

loyal and harmonious people who are, predictably, well liked by others.

Compromise

This is the style favored by persons who have a degree of concern for

self as well as for others. They confront and negotiate when faced with

conflict but they have a lack of commitment to working towards solutions

which can meet as many needs as possible. Rather, they are prepared to

bargain and are willing to give up some of their goals if others will

give up some of theirs. Thus, they seldom arrive at a solution that

meets all of their needs or those of others but their solutions do allow

some of the needs of all parties to be met. Generally, these individuals

are well liked since they try to listen to other persons” points of view

and because they are willing to give up some of their own desired

objectives.

Win-Win

Win-Win is the style of persons who hold a high concern for self and for

others. These persons confront conflicts and use negotiation strategies

to resolve them. Win-Win is the most constructive style of managing

conflicts since the aim is to bring about decisions or solutions which

are satisfying to all persons involved. This is the ideal prototype for

managing conflict. Because Win-Win negotiators recognize the importance

people attach to their needs, they are not totally preoccupied with

meeting their own needs but are prepared to try to understand what

others needs as well. Thus, they try to make certain that all views are

heard and all parties have their needs met. Their commitment to finding

solutions which are acceptable to all, as well as their sensitivity,

belief in others, and objectivity make them good colleagues and

constructive family members.

Successful conflict management

The description of conflict management styles provided above suggests

that there may be heavy intrapersonal and interpersonal costs associated

with the use of any method that has a “lose” component. The compromise

method involves fewer costs but limits the degree to which individuals' needs can be met. The problem solving (Win-Win) method is the ideal

approach to resolving conflicts because it maximizes the degree to which

individuals' needs are met and, at the same time, its use helps to avoid

negative affective or interpersonal consequences. The Win-Win approach

involves a number of steps:

Identifying the conflict or issues and communicating this in objective and descriptive terms.

Requesting others to work toward a mutually acceptable solution.

Providing encouragement to all parties to state their perceptions of the situation and to outline their needs.

Generating a list of possible solutions through brainstorming.

Choosing an option which meets as many needs as possible and is acceptable to all.

Evaluating the solution subsequent to implementation to ensure that it has, indeed, met the needs of all concerned.

The use of this approach tends to result in constructive interactions, with family members expressing their own needs clearly and directly, and listening to try to understand each other’s point of view. The problem solving approach is based on a value that all members' needs are important and on a commitment to finding mutually acceptable solutions. Using this approach the abuse of power, manipulation and withdrawal are minimized. Family interactions, in general, become more constructive and harmonious and relationships are strengthened.

The skills of conflict management

The problems faced by many families in the child welfare system are

complex and multifaceted. Undoubtedly there are many factors that have

created and helped to maintain these problems. One important element is

the lack of effective conflict resolution and, consequently, minor

disputes often escalate to crisis, negative feelings develop,

relationships become chronically strained and dysfunctional patterns of

interaction emerge.

Improving the ability of families to manage conflict can be an effective way of providing help. In our experience, conflict resolution skills can be improved by teaching families the following:

knowledge and awareness of conflict management styles and approaches;

skills in initiating positive confrontation;

communication skills; and

knowledge and skills in using the problem solving (Win-Win) method.

In this section, a brief description is provided for each of these elements.

Knowledge and awareness of conflict

management styles:

The basis for developing effective conflict management skills is

knowledge regarding approaches to managing conflict and a high level of

awareness of one’s own style and approach to managing conflict. Much of

the material outlined in the first sections of this paper can be

presented to families to develop their understanding of conflict

resolution approaches and styles. Then family members can be helped to

analyze conflict resolution in their own family. Through becoming aware

of their own and other family members' conflict management styles,

individual family members can learn to change and modify their

unproductive behaviors into more constructive ones.

The skills of initiating confrontation

positively

How an issue is raised often determines whether the conflict can be

effectively resolved. Although often inadvertently done, many people

initiate confrontation in a manner that produces defensiveness, anger or

an aggressive response. The goal is to teach family members effective

ways of initiating positive confrontation through making opening

statements that do not produce negative reactions which reduce the

chances for a constructive resolution. Opening statements should be

non-threatening, identify problem behaviors in observable terms, outline

the feelings incurred, and describe the effect the conflict has on the

initiator. In short, family members require the skills to communicate

their needs openly and directly and to request other family members to

help resolve problem issues.

General communication skills

In addition to the skills of initiating confrontation, family members

need a number of other communication skills to effectively manage

conflict. Most important among these are the skills of active listening

and accurate empathy. Using these skills, individual family members can

encourage each other to share their opinions and feelings, acknowledge

those views and feelings, check for accuracy and completeness in their

understanding of explicit content, and identify underlying meanings of

other persons' communication (Johnson, 1986; Miller, Wackman, Demmitt

and Demmitt, 1980).

Problem solving technique (Win-Win

method)

Finally family members should learn the most constructive method of

resolving conflict, the problem solving (Win-Win) technique. As the name

suggests, this approach involves focusing on issues rather than on

personalities and arriving at a resolution that maximizes the extent to

which all parties can meet their goals.

This approach provides a rational, open and constructive method for resolving conflict. It involves a two-way communication process in which a conflict is defined mutually, proposed solutions are identified, agreed to, implemented, evaluated and if needed, modified. The model incorporates many of the techniques described by Warshaw (1980), Glasser (1969), Gordon (1970) and Johnson (1986). The major steps are as follows:

Confront the problem. Individual family members have the responsibility to face issues and initiate resolution of problems by describing the concern, stating their needs and asking for the cooperation of other family members in resolving the conflict. This can be effectively accomplished through the use of opening statements (as described above).

The problem is defined mutually. It is important for family members to use their active listening skills during this step. They should encourage each other to share their opinions and feelings and confirm their understanding of other members' positions. This process should result in a clear identification of each person's needs.

Negotiate a solution. One of the most effective approaches to negotiating a solution is to generate alternatives through brainstorming. When as many options as possible have been identified, the process of evaluating and narrowing the options may begin. This step can be time consuming and frustrating, and finding an acceptable solution may seem elusive. However, given adequate commitment and due effort, this process should lead to a strategy which is mutually acceptable to all and meets as many needs as possible.

Make a joint decision, implement the solution, monitor and evaluate. Modifications and changes may subsequently be made. It is an important feature of this approach that the decisions taken are tentative and subject to renegotiation should it turn out that some important needs are not being met.

Although this approach is the preferred method for resolving conflicts, it should be noted that it is not always feasible or appropriate to use it. Limitations of time, the impracticality of devoting the effort required in every instance of family conflict or other circumstances may preclude the use of the problem solving approach. Recognizing that different situations call for different approaches (Adler and Towne, 1987) family members should not only master the Win-Win method but develop the ability to choose the most appropriate conflict resolution method for the given situation. For example, if the substantive issue is of little importance and the other person has a considerable ego investment in a situation, then the “Lose-Win” approach may be used to smooth over the conflict. However, whenever major issues are at stake, the “Win-Win” approach should probably be used.

Strategies for teaching families the skills

of conflict management

As mentioned earlier, child care workers who work in family settings are

in a unique position to help families improve their conflict management

practices. First, they can provide training to family members to help

them understand the dynamics of conflict and to help them learn skills

for managing conflict more effectively within the family. Second,

because they work for extended periods of time within the home, they can

help family members implement their new understanding and skills.

Helping in this manner, by providing concrete, practical services, is

congruent with the philosophical base from which child care has

traditionally taken its direction (Gabor, 1987). Our experience suggests

that workshops combined with in-home training can be an effective means

of delivering such training.

There are a number of advantages to providing training within a workshop setting. First, a group of families can participate together and offer each other support and encouragement. As well, family members have an opportunity to see that their problems are not unique and that other families are struggling with the same issues. Second, the sessions can have a strong educational focus, particularly when the theoretical material is presented. This has the effect of casting participants in the role of learners, much welcomed by many people who have had long involvements with the child welfare system as clients. Third, the workshop setting provides a relatively non-threatening environment for learning new skills, affording family members opportunities for practice and rehearsal in simulated situations where real family issues are not at stake.

However, by itself, workshop instruction is unlikely to be adequate. Although most family members can learn the theoretical material and the skills as a result of their workshop participation, many find it difficult to apply the information to their own situation or implement the new approaches at home. Individualized, family-specific instruction can help overcome this problem by personalizing the material.

Child care workers can facilitate this process by asking family members to analyze their own and other members' approaches to conflict resolution. Then workers can help members reflect on recent conflict situations, building the latter’s awareness of conflict resolution practices within their family. Next, workers can help family members identify how, through the use of the Win-Win method, previous conflicts might have been handled more constructively. Finally, workers can help family members role-play the previous conflict, encouraging them to use the new techniques.

Because child care workers are in the home for extended periods of time, actual conflict situations are likely to occur while workers are actually present. Such occasions can provide excellent opportunities to help the family implement the newly taught approach. Workers can coach family members in vivo, support their efforts and provide them with feedback. Such situations also provide workers with the opportunity to identify any gaps in family members' knowledge or skills and to supplement previous training where necessary.

Summary

Many families are unable to effectively resolve the conflicts which are

an inevitable part of family life. Ineffective or inadequate conflict

resolution can adversely affect other aspects of family life and result

in negative feelings, deteriorating relationships and dysfunctional

patterns of functioning. A novel approach to helping such families is to

teach them the skills of conflict resolution. Although this is but a

single intervention it can have a generally helpful impact in troubled

family situations. Our experience suggests that such training can be

provided in two stages: group training in a workshop format followed by

family-specific training in the home. Family child care workers are in

an excellent functional position to deliver both phases of the training,

although some workers may need to upgrade their instructional skills.

General instruction in conflict resolution followed by family-specific

in-home training can become a powerful means of helping troubled

families.

References

Adler, R.B., and Towne, N. (1987). Looking Out/Looking In: Interpersonal Communication. (5th ed.). New York. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Gabor, P.A. (1987). Community-based child care. In C. Denholm, R., Ferguson and A. Pence (Eds.), Professional Child and Youth Care: The Canadian Perspective (pp. 155-174). Vancouver. University of British Columbia Press.

Gamble, T.K., and Gamble, M. (1982). Contacts: Communicating Interpersonally. New York. Random House.

Graham, G. (1980, March). How to settle conflicts. In G. Graham (Ed.), Applied Management Newsletter. Wichita. National Association for Management.

Glasser, W. (1969). Schools Without Failure. New York. Harper and Row.

Gordon, T. (1970). Parent Effectiveness Training. New York. American Library.

Johnson, D.W. (1986). Reaching Out: Interpersonal Effectiveness and Self-Actualization (3rd ed.) Toronto. Prentice-Hall.

Miller, S., Wackman, D.W., Demmitt, D.R., and Demmitt, NJ. (1980). Working Together: Improving Communication On The Job. Minneapolis. Interpersonal Communication Programs.

Phelps, S., and Austin, N. (1974). The Assertive Woman. San Luis Obispo. Impact.

Stepsis, J. (1974). Conflict resolution strategies. In J.W. Pfeiffer and J.E. Jones (Eds.), The 1974 Annual Handbook of Group Facilitators (pp. 139-141). La Jolla. University Associates Publishers.

Warshaw, T. (1980). Winning By Negotiation. New York. McGraw-Hill Brook.

This feature: Ing, C. and Gabor, P. (1988). Teaching conflict resolution skills to families. Journal of Child Care, 3, 6. pp. 69-80.